Being easy to work with: how I approach editorial feedback

Have you ever felt ‘told off’ by someone about your writing?

As a copy-editor, I’m essentially giving ‘feedback’ on an author’s writing through comments and author queries. When my client receives this feedback, my top priority is that they feel encouraged and clear about what they need to do next. And never, ever ‘told off’ or reprimanded.

I’ve had to learn the technical aspects of doing this, from marking up PDFs to using comments and track changes in Word. But editing work also includes having good interpersonal skills. I know that a key ‘soft skill’ as an editor is my ability to ensure the feedback process stays respectful and constructive, not adversarial. And I also know my clients appreciate that.

Over the years, I’ve learned that although it may feel that writing a comment or query and sending back to the client should be speedy, it’s vital to take a little time over it. To help make good writing great, the ‘how’ of the feedback matters as much as the feedback itself.

In this post, I share some approaches to raising queries and adding marginal notes (basically, comments in Word) when working with authors.

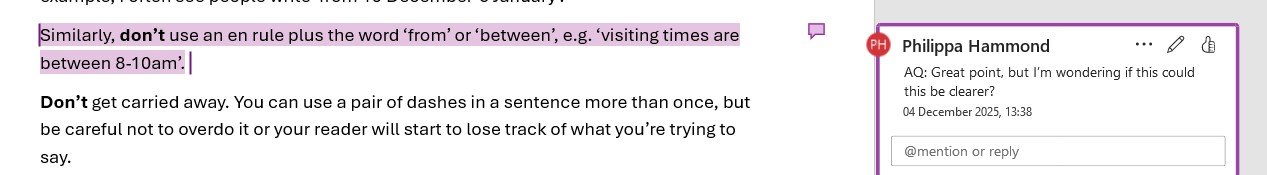

This is how an author query might look in Word

How a copy-editor can make editorial feedback feel more constructive to writers

Beyond in-depth knowledge of grammar and style rules, the art of being able to phrase feedback and queries carefully is one of a copy-editor’s most important tasks. The most thoughtful editors think before they type.

A copy-editor is often one of the first people to read a piece of writing in detail. They perform the unique role as an ally for both the reader and the author. If they can improve on the writing, the reader and author both benefit (as does the publisher).

There was an excellent session at METM25 by Susan Frekko called ‘How to give constructive feedback to writers (or anyone)’. In the session, Susan asked us to work in pairs and role-play an editor–writer scenario, with the aim of putting ourselves in the writer’s shoes.

In this role play, I was a first-time writer and my colleague was the editor. So I got to experience what it would be like to have someone critique my work in a way that was not constructive. It wasn’t pleasant.

In real-life work, I always remember that the text belongs to the author, and I review my own phrasing of queries and comments before sending them to the author. When making editorial suggestions and recommendations, I must put myself in the writer’s shoes. When I query something with a client, I often rephrase that query several times after really asking myself how I would feel if it was directed at my own writing.

Before I hit send, I ask myself:

1. How would I feel receiving this?

2. Does this feedback do more than just point out problems?

Working with a partnership mindset

When I’m editing, I view my relationship with the client (the author) as a partnership, not a confrontation. They wrote the content. The final call is theirs. Full stop.

I’m there to cast a gently critical eye, to make suggestions, working alongside them. Not as someone who is ‘marking’ their work. The editor is not there to prove they are the better writer, nor are they there to rewrite a text (unless that’s what has been agreed).

First-time authors may not be familiar with the editorial process. If they open their draft and find pages of tracked changes and long notes in the margins without carefully worded reasoning, it may not be what they were expecting.

I love this quote in the book The Copy Editor’s (Life)Style Guide: Maintaining Your Joy (and Sanity) in a Rapidly Changing Profession by Jameel Pittman:

‘If given a choice between working with an average copy editor who is a joy to work with and a rock-star-level editor who is a complete pain in the ass, I’d wager that most people would rather work with the former’.

A piece of writing will often contain some strengths that can be developed further, so one approach is to start by identifying those and praising them, so the writing can get to publishing stage.

The editor’s role is to recommend improvements, which of course the author is free to disregard. If you provide excellent feedback but you phrase that feedback poorly, it will fall flat.

The art of phrasing author queries

There’s a knack to framing your questions and comments (known as author queries) when editing, and there are even courses that will help you learn how. As an experienced editor I also use my professional judgement to know when to edit and query, and when not to. And when to rethink.

I recently caught myself writing a somewhat knee-jerk response comment to a client, and I knew I had to think of a way to rephrase it. Here’s a checklist I find helpful:

1. Use ‘we’ language. (as long as it’s appropriate to the author-editor relationship.) Instead of saying, ‘Your sentence is unclear’, how about ‘Could we rephrase this to make sure it is clear to readers?’.

2. Explain reasoning. Instead of ‘delete this sentence’, ‘I wonder if this sentence might work better like this…’.

3. Offer options. Instead of ‘This is unclear’, ‘I see what you’re trying to say, but how about?’, or ‘Perhaps you could break this down into separate points like this…?’.

4. Flag repeated issues just once. I use general notes for global changes (when there are systematic issues with a manuscript), and/or a style sheet note, e.g., ‘I’ve standardised these to [X] format throughout. Let me know if you’d prefer a different approach and I can adjust them all.’

5. Open questions. It’s also a good idea to avoid closed questions (ones that elicit a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer) and instead offer alternatives that help to illustrate your point.

Offer editing solutions, not just problems

The editor is there as an ally (cheerleader, advocate, etc.) for their client’s written work, so simply highlighting what is wrong with their writing is unlikely to move the project closer to the finish line. Again, when pointing out a problem with a sentence, the editor could suggest some alternatives that the author could think about. This continues the collaborative approach.

Explain edits and queries

Hopefully, a copy-editor will be working to a specific style guide or will be building a style sheet for the client/author. Without one, inconsistencies creep in and decisions become ad hoc.

With this style sheet, the editor and author/client will have an easy point of reference to explain any changes that are repeated throughout their text.

For example, the editor might say, ‘For consistency with the style guide, I have amended this to…’.

Copy-editors do also check facts, both within and beyond the text itself. They flag, for example, an obvious error or a time sequencing mismatch when a fact clashes with one stated elsewhere in the text. Sometimes, this needs to be queried, always bearing in mind that the factual error is most likely to be a simple error, rather than a heinous howler.

What if the feedback is truly difficult?

It’s rare that this happens, but the best approach is to email the writer, first commenting on the text’s strengths and suggesting a meeting to go over spots that feel unclear or that could be improved to help the writing achieve its goal.

How does feedback happen in translations?

Because I’m also a translator, I wanted to mention how feedback works in translations, too. I apply the same principles as I’ve outlined above. In some ways, the challenge is even greater because you’re walking a tightrope between more than one ‘author’ voice.

There’s often more than one translator working on a text, and that translator is called the ‘reviser’. The reviser must revise the first translator’s translation thoughtfully, carefully considering what can be improved in the translation while also acknowledging the translator’s (and original author’s) style.

Again, it’s vital that the reviser words their queries to the first translator in a respectful and considerate tone, avoiding the temptation to ‘mark’ their work, understanding that the ‘correct’ translation is often subjective.

The bigger picture

What motivates me when editing is the shared goal of making your writing the best it can be. I skip the nitpicking and focus on changes that improve flow and meaning.

It’s easy to forget that, at the other end of the email is a real human receiving the feedback; someone who may have already spent hours researching and writing their text. When I use collaborative language, explain reasoning and offer options, for authors this makes editing feel less like something they might dread and more like a partnership.

I’m happy to say that several clients have told me that working with me has changed how they think about editing.

If you’re looking for an editor who catches small inconsistencies, retains your voice, and has a collaborative, supportive approach, I’d love to hear about your project.